O. Rufus Lovett, Part 1: Early Days, Texas Monthly and Beauty in Long Term Projects

This is part 1 of a 2-part interview by guest contributor Matt Valentine.

When I reach O. Rufus Lovett by phone, I warn that I’ve just had oral surgery and might have difficulty speaking clearly. “I might talk a little funny,” I say, “because I’ve got this mouth full of stitches.”

“Well I talk funny because I’ve lived in East Texas a long time,” he says.

His voice is just one component of Lovett’s disarming southern charm—he speaks slowly but with a quick wit, like the narrator in a Mark Twain story. No doubt that charisma has ingratiated him to the many communities he’s documented throughout Texas and the southern United States, on magazine and newspaper assignments, and for personal projects that have so far produced three books.

Lovett’s photography has been widely published and exhibited, and is in the permanent collections at the Harry Ransom Center at UT Austin, the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, and the Birmingham Museum of Art. His documentary work for Texas Monthly has been recognized by the Alfred Eisenstaedt Awards, administered by Columbia University. For more than three decades, Lovett has taught photography at Kilgore College, a two-year school in East Texas. In 2005, the Minnie Stevens Piper Foundation of San Antonio honored his work as a photo educator, naming him a Piper Professor.

What’s the “O” for in O. Rufus Lovett?

My first name is an initial. It’s just O, period. My mother was named Opal. My Dad was also named Opal. They named my older sister Opal when she was born. And then they gave me just the O initial instead of the name Opal.

When did you first start taking photos? Or were you too young to remember?

My high school was actually on a university campus, so we had student teachers and so forth. My dad just worked up the hill, in his office at the university. My mom taught there in the English Department. And so everybody kind of knew everybody—you know, small town, Jacksonville, Alabama. I was approached by the English teacher — who was the sponsor of the newspaper — and another lady who sponsored the yearbook. I was asked if I would like to do photographs for those publications. And I thought — yeah, that’d be cool, you know. They thought they had a perfect “in,” because my dad had a ways and a means of getting the work done, since his photography studio was just up the hill at the university. And so that’s kind of where I began getting serious about photography, because I was doing production work from the get-go, and printing with my dad at the university was a major start and major influence on what I was doing.

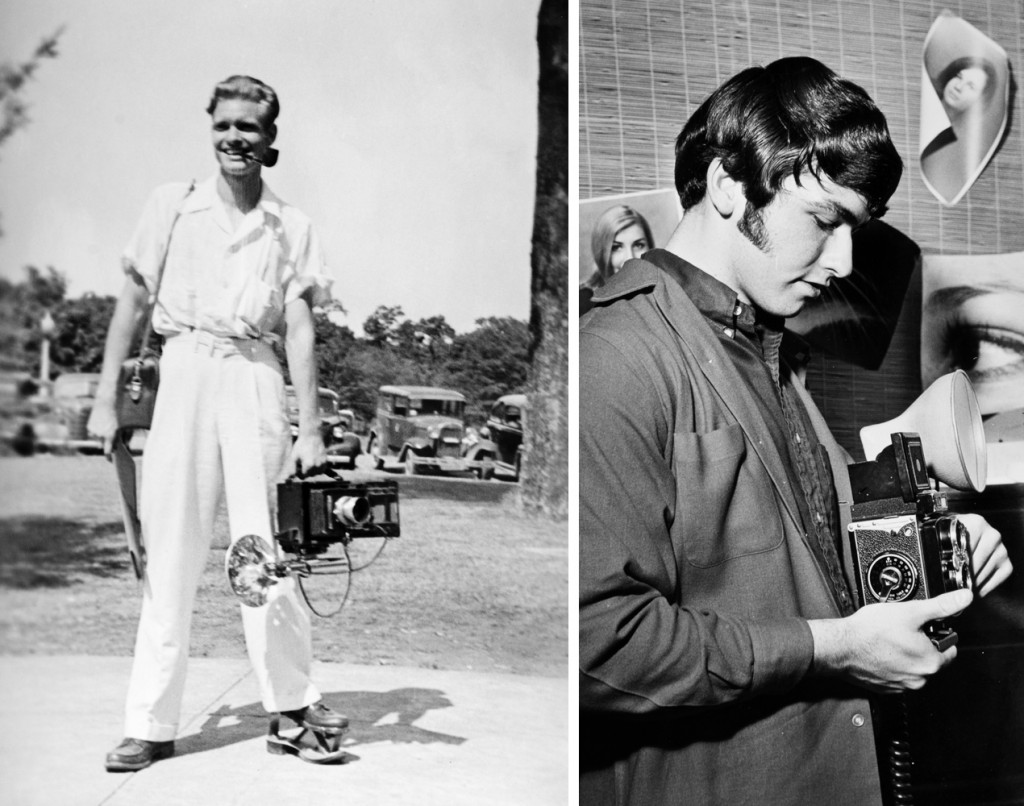

Left: Opal Lovett. Right: O. Rufus Lovett, age 16.

You included one of your father’s photographs as a frontispiece in your first book, Weeping Mary, and your own photographs seem to share some of the same mood. Do you think your father’s photography influenced your work in other ways, in other projects?

Yeah, quite a bit. He was a portrait photographer as well, and photographed events, and I would go along with him and assist. I used to carry the old blue flashbulbs along, back when he was shooting a Crown Graphic, and I would collect the spent flashbulbs. Or I would stand on a chair or table somewhere with an auxiliary flash to fill in light. So he taught me at the beginning how to master lighting techniques, as guidelines. I learned a great deal from him in terms of good basic fundamental things.

Also, you know, his work was very applied photographic work. It was meant to sell and send out for Associated Press news releases for the university. But occasionally, he would go out and photograph on his own, and those are the photographs I admire most of his work. But he didn’t do that as often—he was consumed with his work at the university and he loved every bit of it. So that work that he did as an applied photographer was his personal work as well. And so it meant a lot to him, and I did learn so much from those early experiences as a child. And watching him print in the darkroom. I can remember sitting on a stool, just barely able to look over the sink, watching the prints come up in the developer, which was always fascinating as a child.

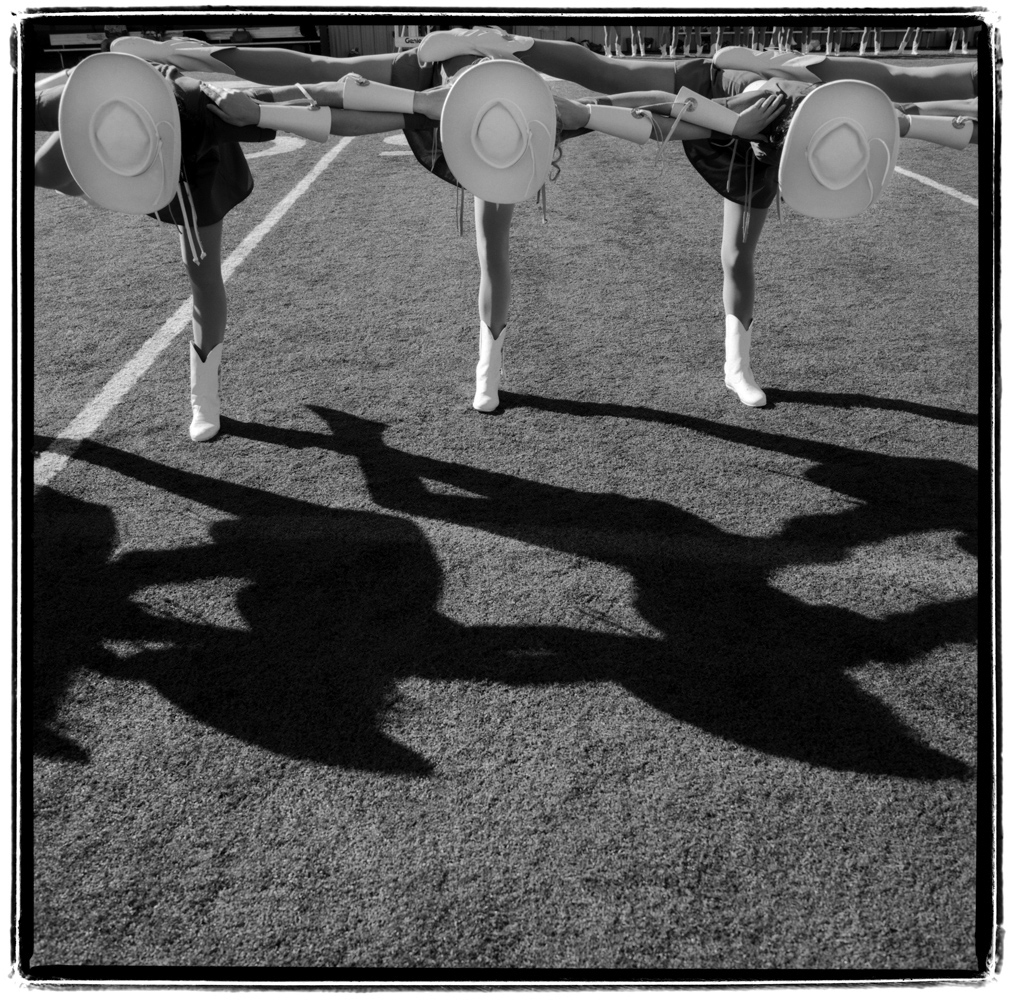

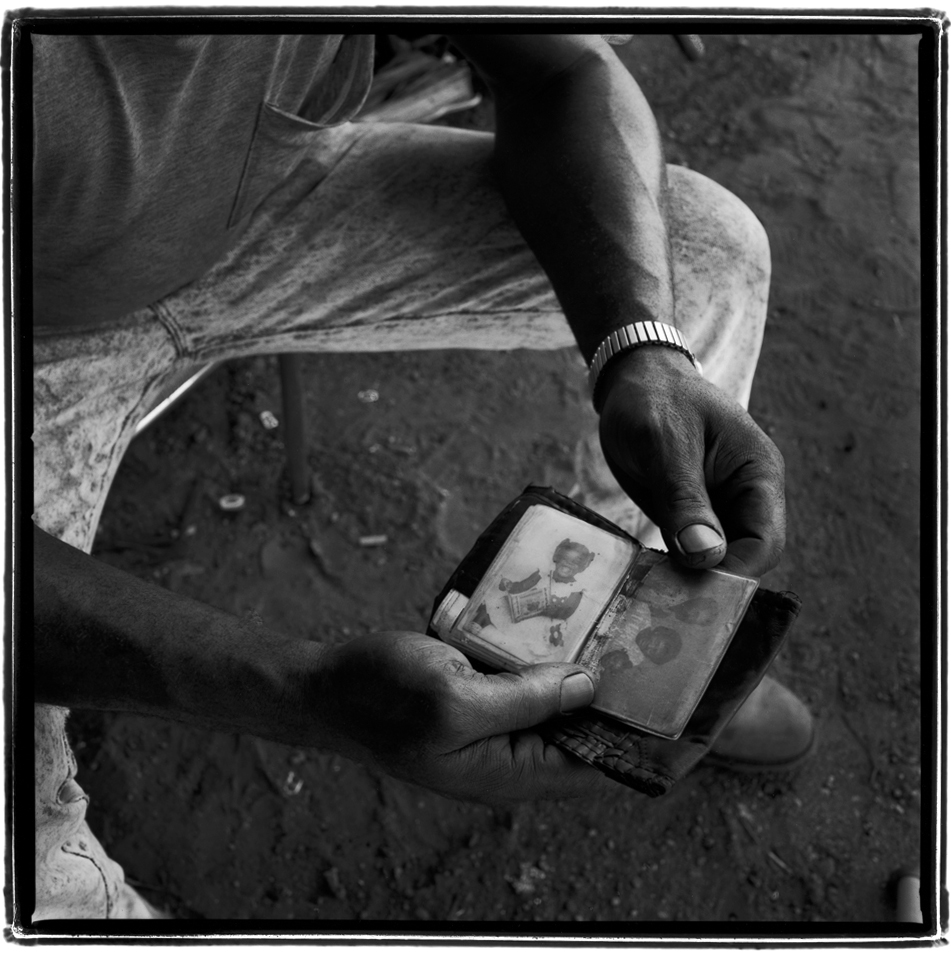

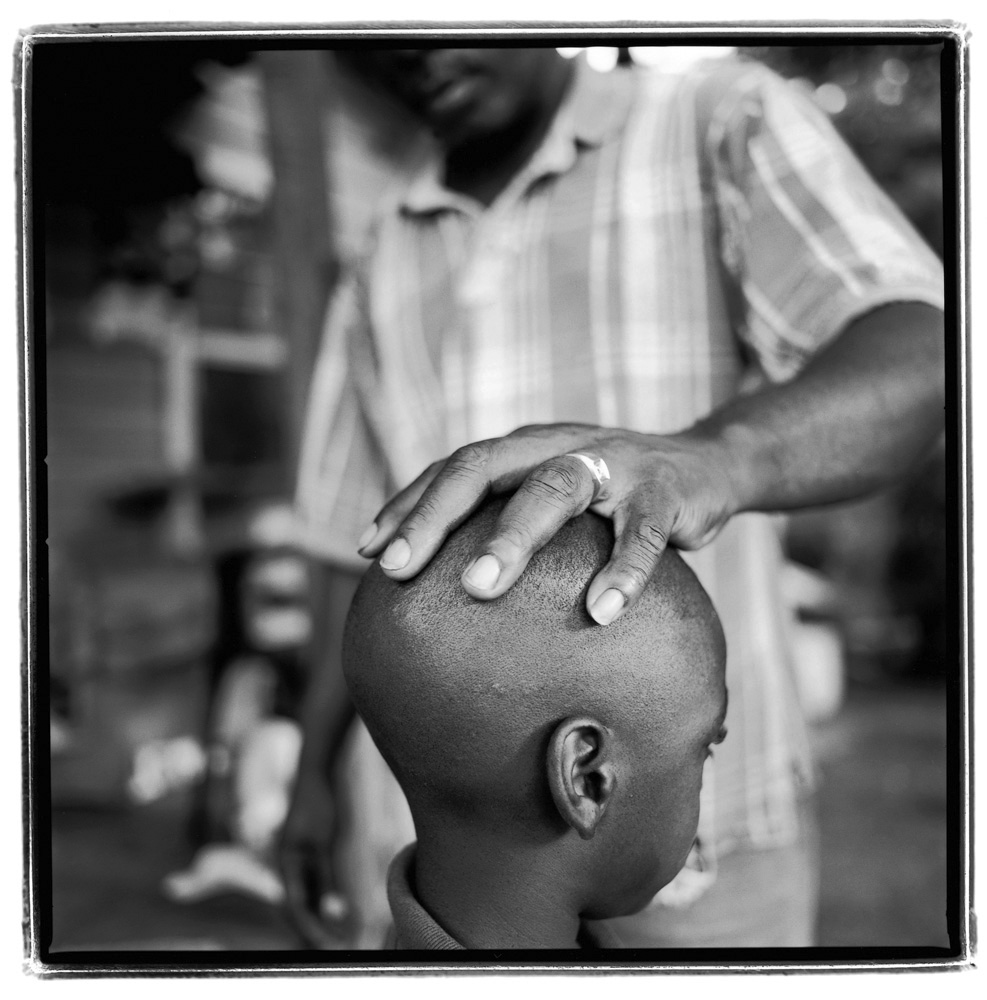

Your photographs in Weeping Mary are a very intimate portrayal of an insular community, a tiny town that is almost entirely African American. As a pretty conspicuous outsider, how did you approach that project?

I don’t really start out with a game plan when I’m documenting a group of folks or, in this case, I guess you’d call them subcultures within our culture. In the case of Weeping Mary, it was critical that I visited many times without a camera to get to know the folks before I even got a camera out.

© O Rufus Lovett

It was an interesting situation there, because people want to know “why are you taking our picture?” and often times people in a community of that nature don’t understand the beauty an outsider might see within that community. It’s difficult for anyone who lives there to comprehend that. Not due to ignorance — anyone would feel the same way, like “why would you be photographing me?” There was just a certain beauty there that I wanted to document on many levels.

To introduce myself, I just tried to get to know the folks, being from a small town certainly helped my ability to communicate, get along with the people there. I made great friends there. That was the beginning of that—just getting to know the people. Now, in that situation also, it was kind of unique, because a friend of mine over in Nacogdoches, Texas, which is not far from Weeping Mary, was the editor and publisher of a newspaper, and as a matter of fact, he’s the one who introduced me to Weeping Mary. He mentioned the name of the community, which piqued my interest, and he wanted to do a couple little picture page spreads about the community. So we did one called “Children of Weeping Mary”, and another one, “Christmas at Weeping Mary,” and published that in the newspaper, and then that of course gave me some credibility, because if we’re doing a picture story about the children, or about Christmas at Weeping Mary, you can introduce that as a project, and make a purpose for my being there.

And then I continued for years after that. Continued photographing and visiting, and enjoying that community, and then it developed into the Weeping Mary book.

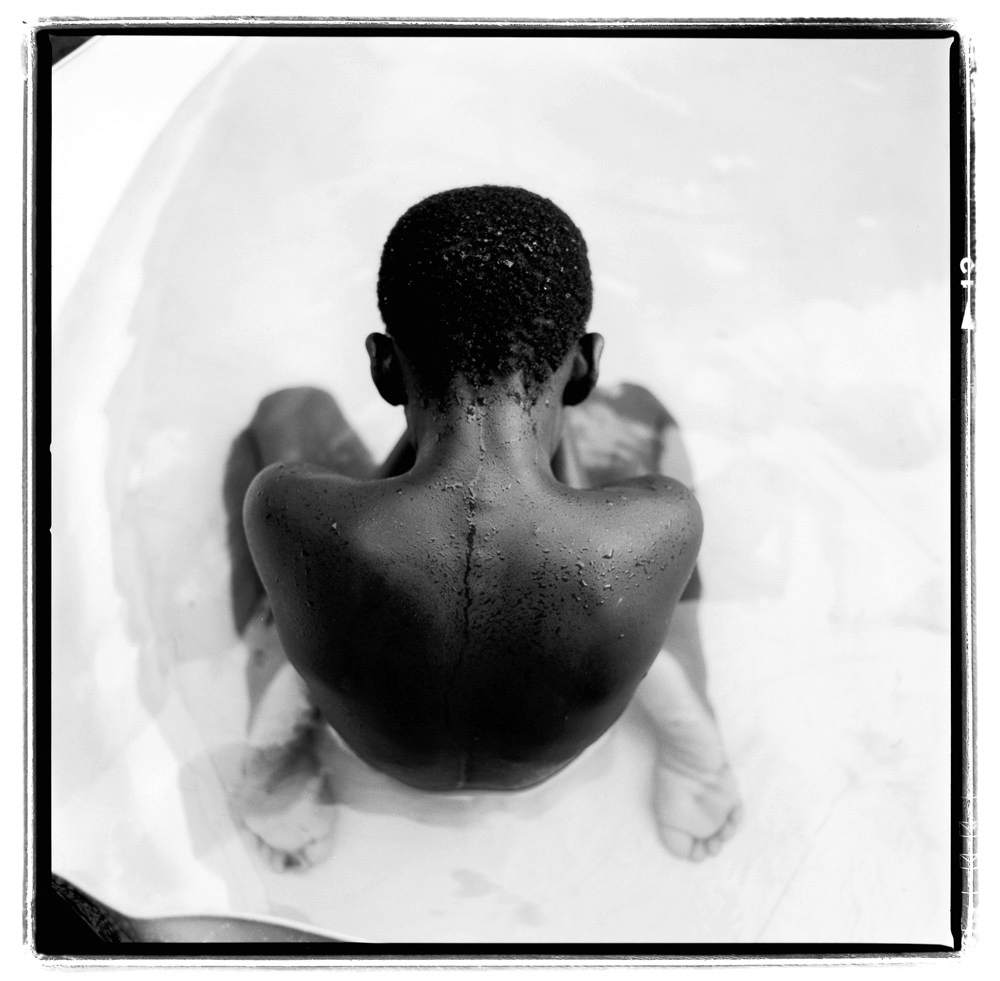

The photos seem really naturalistic. But some of these were made with a little more sophisticated artificial lighting equipment, right?

It’s always the situation that dictates what you’re going to do about lighting in a photograph. Often times, I would use the existing light of course, and many times a tripod. And other times, depending on the situation, I would use an auxiliary flash, often modified by a small softbox, to soften the quality of the light, but still nice and directional, and marry that light with the ambient light in the environment.

I seem to remember a story about one person you photographed there as a child who wasn’t very happy with that photo as he got older.

There were a couple of cases like that. It might have been the swimmers photograph. Two little boys in their underpants, swimming in a little backyard pool. Later, they were kinda teased at school about that photograph. I mean, it was published in Texas Monthly. The teacher brought it in — not to embarrass them, but to show them that Weeping Mary was published. It kind of embarrassed them a little bit, so as those guys grew a little older, they expressed, uh, a disinterest in that photograph. But nothing ever came of that, other than that they didn’t appreciate it right away, because it kinda embarrassed them when they were in school. I have a feeling they’re fine with it now. They grew up to be rather large football players, and so luckily they didn’t hold it against me too badly.

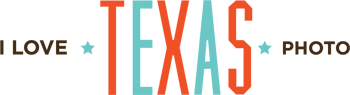

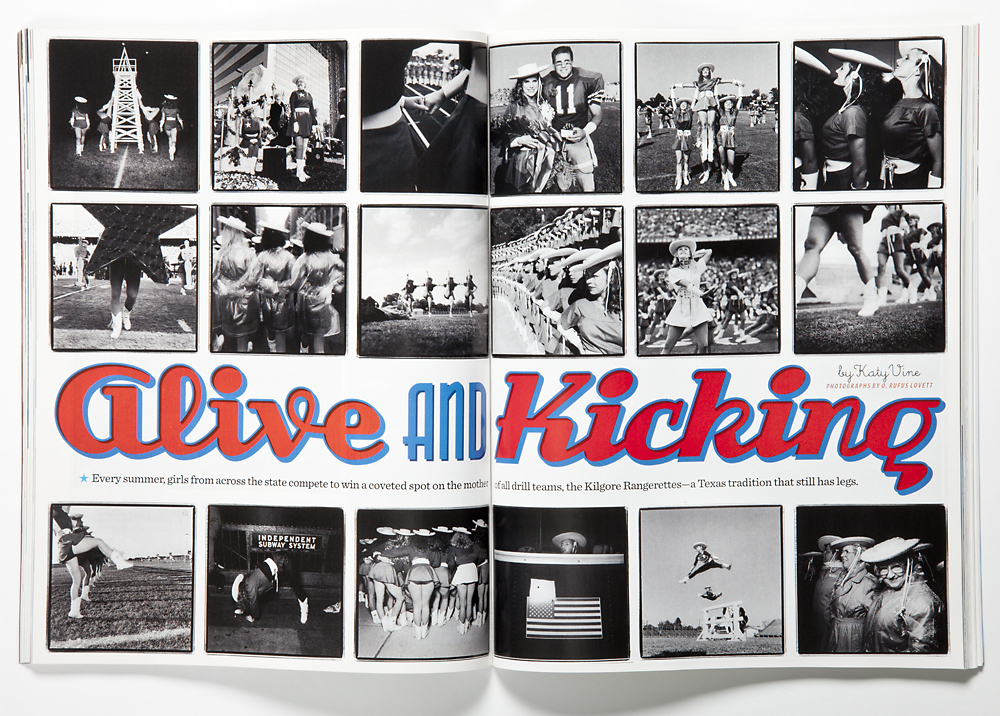

Your second book, Kilgore Rangerettes, grew out of long photo essay you did for Texas Monthly—an unusually long essay, by contemporary standards. Do you think there are some stories that are really best told with many photographs?

This has a lot to do with the economics often times, you know. Magazines have to support themselves, and they have to make room for advertising, and they have only so much space. It is unusual that so many photographs were used in that particular photo essay. Scott Dadich was the creative designer at that time at Texas Monthly, and I think he did a great job of placing as many photographs as he placed in a relatively small space. I was surprised that they used that many, but using that grid format that they used on some of the pages, he was able to introduce numerous images, which was a good idea I think in this case–to define the project well. There was quite a volume of work over a period of time, a decade or so, I suppose.

© O. Rufus Lovett

But you know, space constraints have a lot to do with that long photo essay occurring in publications these days, which is why it’s so important for a photographer, when he’s out photographing a project, especially for a magazine, to make every picture kind of a stand-alone type of photograph. I teach about this in my photojournalism classes. In a photo essay, each photograph is like a paragraph, and then several paragraphs make up the essay. And so, if each photograph can stand alone as a complete thought, and then when put together with other photographs, makes sense, that allows magazines to complete a photo essay with a brief amount of space. So that’s an important issue and always will be, and yeah, I can remember the old days when Life magazine and Look magazine had these really expensive photo essays. It was beautiful to see them. We don’t see that happen much anymore these days, unfortunately. But I’m sure it’s mostly economics.

You’ve published in many magazines and newspapers, but it seems to me that Texas Monthly has really been the best home for your work. Would you characterize it that way?

Yeah I would say so. And there’s some really interesting human condition kind of work — which is my main emphasis I suppose — with People magazine, of all publications. They’ll do these little features on communities and different folks from time to time and they’re quite nice. They’re usually found in the back of the magazine behind all of the celebrity stuff. I did this really neat story with People one time — it was a 70-year-old man who went back to 1st grade to learn how to read, up in Missouri.

It was a wonderful little photo essay as it turns out. And then I’ve done stuff for Gourmet up in New York. I did this whole thing on Dominican culture and Dominican food. As a matter of fact that’s how we got this barbecue project going — a story I was doing for Gourmet with Robb Walsh (acclaimed food writer). That’s when we first met. Then later we did something for Saveur Magazine on barbecue, and we decided to carry it on and do that BBQ Crossroads book. Magazine editorial work sometimes influences you in a variety of directions—you never know how that’s gonna snowball and what it’s going to bring next. It’s kind of an interesting aspect of my career. The magazine work I’ve been able to do, I’ve been privileged to do it. Starting with Texas Monthly and going from there. People usually just call Texas Monthly to get to me. I don’t even have a website.

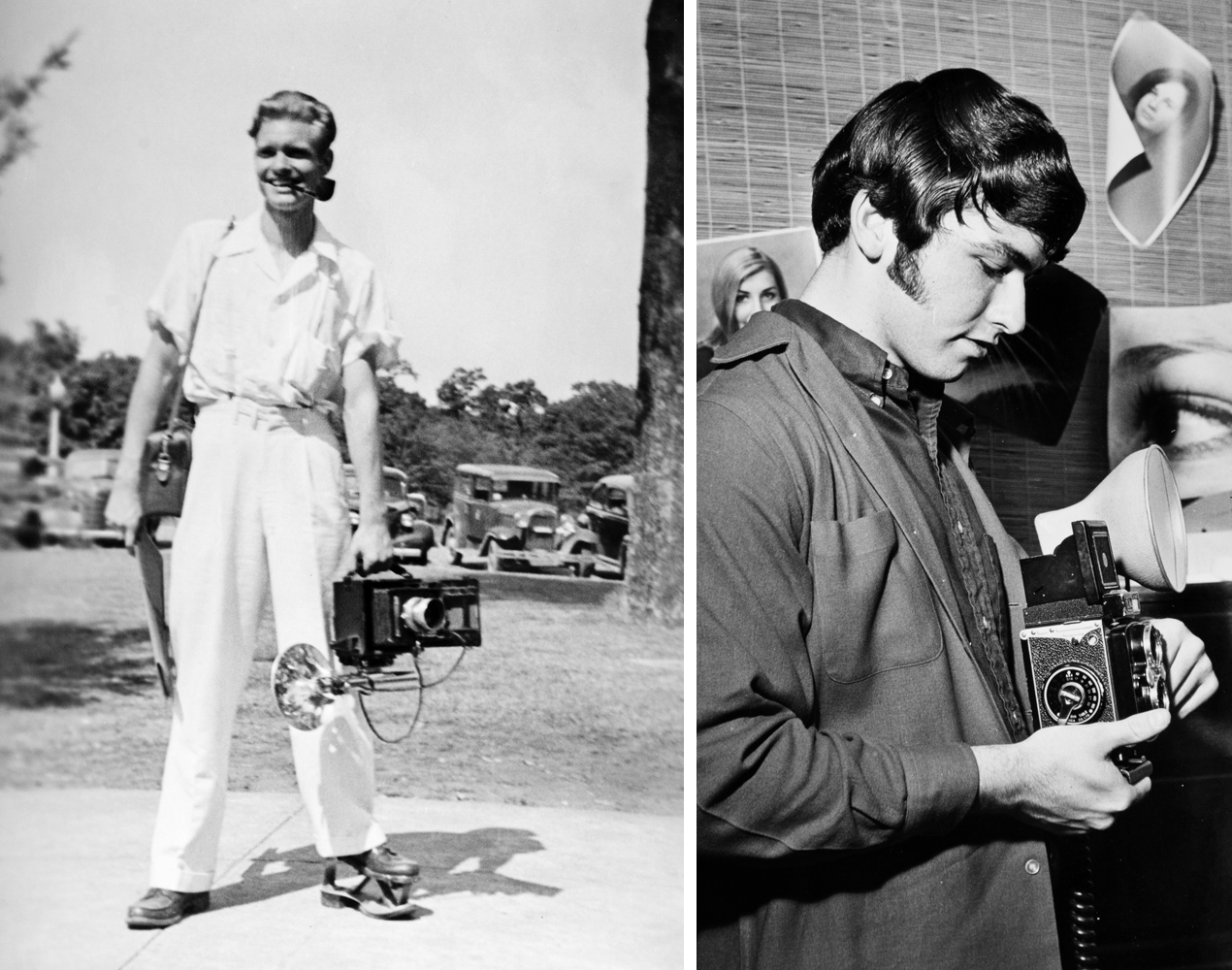

One of the things I love about the Kilgore Rangerettes book is that there are several photos of the Rangerettes using cameras. For me, the cameras locate the photographs in time, because the uniforms don’t change that much, and the setting doesn’t change much, and these black and white photos could really be from forty or fifty years ago—except we’re reminded that this is actually contemporary, because we see one of the Rangerettes using a little point-and-shoot camera or a digital camera. Was that your intention? Including that little detail as sort of a time stamp?

I’ve always been a little fascinated, for some reason, with tourists taking pictures of scenes. When I travelled to Asia I enjoyed photographing the tourists that were photographing the monuments, or their friends in front of the monument. I just found something delightful about photographing photographers photographing what they’re interested in. And so that kind of carried through, because the Rangerettes constantly take pictures of one another, whenever they go to an event or even a rehearsal or whatever the occasion, they’re constantly taking photographs of themselves. I just find an interesting irony in those kind of photographs. But you’re right, that is a key that kind of illustrates a timeline for those photographs. Otherwise they’re pretty much timeless, unless you look real closely at the type of bleachers that are in the stands, or the kind of pavement that’s more contemporary than a 1940s or 50s type pavement, you may not know what decade some of those photographs were made in.

Your new book, Barbecue Crossroads, is a significant departure from the first two. The most immediately obvious technical difference is that these are color photographs, whereas your previous work is predominantly black and white. Can you talk about the decision to use color?

Originally, Rob Walsh the writer — he and I travelled from Texas to the Carolinas and back, including Arkansas, Tennessee, Alabama, a little bit of Georgia and the Carolinas, and a couple places in Texas as well — and we originally were gonna do the book in black and white. It was gonna be, you know, kind of an edgy black and white kind of thing. But as I started photographing this, the color played such an important role in these little joints, and with the food subjects themselves, so I made the decision to request the change on that and just do the whole thing in color, which I think fit that project well. That was a decision based on the environment and the circumstances, which I felt were best interpreted in color.

However, one other difference between that book and the other two is that I was working with someone else, a wonderful, very knowledgeable food writer, and a lot of those photographs dealt with illustrating his points of view about the places that we went to. My point of view was also teased in there as well, in some of the other maybe more pictorial type images, and some of the documentary work. A lot of auxiliary lighting was used, however not always–I used a lot of window light when it was possible. There’s a lot of variety of techniques that were used in making that photographic documentary on the Barbecue Crossroads book.

I learned this from Mary Ellen Mark years ago, that circumstances dictate everything in terms of how your gonna light it, what medium you’re gonna use. It was all done digitally, instead of film. That played an important role, and the fact that I wanted to use color, so that made some of those difficult circumstances a little more convenient to photograph in, just in terms of the equipment alone. There were a lot of technical influences that dealt with the reasons why we decided to go with color on that.

(Editor’s note: Join us tomorrow when we publish Part 2 of this interview. Lovett talks with Valentine about how teaching photography is changing, and what he sees as the future for his students.)

While completing his MFA in Creative Writing at NYU, Matt Valentine worked full time for the Department of Photography and Imaging at the Tisch School of the Arts, designing and maintaining their “digital darkroom” facilities. He continues to pursue simultaneous careers in writing and photography. Matt’s short stories have won national awards, including (most recently) the 2012 Montana Prize for Fiction. His portraits of writers have been published in the New York Times, Washington Post, USA Today, Los Angeles Times, Men’s Journal, Boston Review, Outside Magazine, O (the Oprah Magazine), and on dozens of book jackets. A Lecturer for the Plan II Honors Program at the University of Texas at Austin, he teaches two undergraduate courses: “Writing Narratives” and “Photographic Narratives.”

While completing his MFA in Creative Writing at NYU, Matt Valentine worked full time for the Department of Photography and Imaging at the Tisch School of the Arts, designing and maintaining their “digital darkroom” facilities. He continues to pursue simultaneous careers in writing and photography. Matt’s short stories have won national awards, including (most recently) the 2012 Montana Prize for Fiction. His portraits of writers have been published in the New York Times, Washington Post, USA Today, Los Angeles Times, Men’s Journal, Boston Review, Outside Magazine, O (the Oprah Magazine), and on dozens of book jackets. A Lecturer for the Plan II Honors Program at the University of Texas at Austin, he teaches two undergraduate courses: “Writing Narratives” and “Photographic Narratives.”