Blake Gordon is a landscape and adventure photographer, who trained as a landscape architect at Auburn University and Design at The University of Texas in Austin. He takes a modern approach to landscape photography, exploring how people fit into the picture. He splits his time between Austin, TX and central Colorado when not traveling.

So, how’d you get started in photography?

I started shooting as a way to explore place during site visits for our studio classes in landscape architecture. During my education we spent extended time in a wide variety of places: southern Utah, New York City, the borderlands of southern California among others. Our first larger outing was a 3 week canoe trip to Algonquin Provincial Park north of Toronto after an intense readings class on ecology. I borrowed my mom’s camera for the trip and never gave it back.

Photography can be part of the design process. It facilitates a deeper reading of the site where a design intervention occurs. You’d go back and forth from the studio to the field, but it’s that initial exploration in the field that grabbed me. That’s when I realized the camera gets you out into the world. And I wanted to explore place, so the camera facilitated that.

The bulk of landscape photography that I initially found is pretty pictures of national parks and while that is appealing, I found it didn’t really fuel me creatively or add much to a cultural dialogue. What is communicated 95% of the time is, “this is beautiful and I wish I was there.” I’ve always been interested in a deeper understanding.

I’m interested in the idea of landscape, how that continues to change, and what that says about culture. Landscape has been described as the meeting point between culture and physical terrain. I find that intersection fascinating.

Do you have any mentors?

I don’t know if I would say that I have any mentors but there are a few photographers I’ve worked with that have been good learning experiences.

Working with James Balog, an amazing National Geographic photographer/artist/conservationist was influential. I helped him design/build some remote time lapse camera systems in 2007 for his Extreme Ice Survey Project. I went to Iceland for the install of the first camera systems. With Jim, it was very much a working relationship but to be with him in the early stages of such an enormous project was very insightful.

I connected with Balog through John Weller, a friend and incredible photographer/conservationist in his own right. He received a Pew Fellowship and has been doing a lot of work for the Pew Foundation as well as continuing to work on a conservation project for the Ross Sea in Antarctica – something that he has been pursuing for 5+ years. We talk a lot about the structure of a journey, learning from the natural world and trying to communicate those profound moments that seem just beyond the boundaries of language.

Brent Humphreys is a friend in Austin who I’ve worked for in Austin and Brent’s work is editorial/commercial oriented. He’s very meticulous and detail oriented as well as constantly pushing to create a better photo. Brent is very design oriented in his thinking and is as interested in project development as much as he is the singular photograph. I find that similar to myself and so enjoy watching how he thinks about photographs.

…the camera gets you out in the world.

What influences and inspires you?

There is a lot of music, art, and ideas out there that inspire me, but experience is the ultimate teacher. I try to keep a creative distance from produced work because I think the best stuff comes out of the process. I do enjoy hearing about how other artists approach their work and work through their process. That is more relevant to me than the work itself.

You have a wonderful body of work from the Nature Conservancy for the latest issue on The Edward’s Aquifer, in San Antonio. Tell me more about the project and how you got involved?

The assignment came through Wonderful Machine. The photo editor, Melissa Ryan, contacted me several months before the shoot. They liked some previous work I had done, namely the Nightwalks body of work. We got to talking about doing a little more of a conceptual shoot rather than the typical illustrative editorial images and I spoke about my interest in how people and landscape interact.

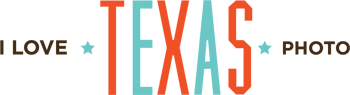

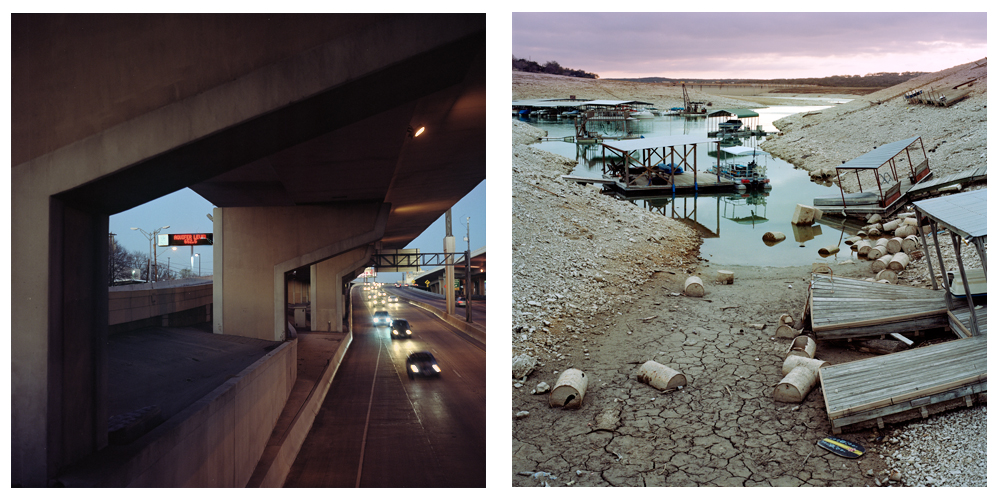

The focus of the story is on the Edwards Aquifer and how The Nature Conservancy is protecting land to protect the aquifer. One inherent challenge in photographing that story is that it is an underground body of water, so I started to look for signs of moments in the landscape where culture and the flow of the water intersect – the recharge zones of ranchers, water table signs along the interstate, sinkholes, spring-fed pools, pumps for the city water supply, etc.

It was a great assignment that I shot for about a month. I stretched it out, but I really enjoy the continued focus and refinement of a longer exploration. I was engaged with the all the way through into the design and layout which is a rare treat. I proposed shooting on medium format square as it would help convey the. We were able to run the images large and on their own page with a consistent pacing which allowed the subtleties and complexities of the situation to come out. The story wasn’t inherently a strong visual one and this really worked well. The layout is beautiful. It looks like a journal.

You shoot some amazing landscapes. How does TNC’s latest issue relate to your personal work?

I was excited to put a lot of resources into the assignment as a commissioned work. I have to push personal work to the point where I am tired of dealing with the idea I am exploring or else the questions will continue to lure me. Melissa came to me wanting my personal vision to come through in the assignment. That was a very enjoyable thing but also comes with a burden of having to produce under different circumstances. The constraints of an assignment are very different than with a purely personal exploration.

I’m really interested in the perception of place and the relationship between people and their environments. This was a great example in that we were looking at how a water system and cultural system interact. I try to step back and think as broadly as possible about those relationships as it lets you look deeply into otherwise mundane things. Part of a photographers is to bring forth wonder. That is easy to do in an exotic location or adventurous moment, but takes bending the mind a little when you’re looking at a water pump or road sign.

The larger focus from a conservation standpoint is to try to make people aware of this water system that there lives depend on. The hard work of public officials and modern engineering has made it so that the general populace doesn’t have to think about all the details when they turn on a water faucet. But that convenient lack of awareness there can put a city, or civilization, on a dead-end path.

In my personal work I also like to step into a realm of thinking that is different from how we ordinarily experience the world. And that is what makes it a valuable exercise.

Do you use a majority of natural light in your work?

Being aware of my surroundings is the first step in my process, so I enjoy finding light wether that is natural or artificial. I will also bring in and use strobes at times – more so with portraiture. I think using found light is important is critical if you are trying to give the viewer an experience of the world as is. I enjoy working with lights but also enjoy a very streamlined process regardless of aesthetic.

I primarily shot natural light until I began the Nightwalks work in which I started shooting urban nightscapes. I found I was more interested in the process of shooting at night than the actual product so I continued to refine how I went about shooting. I went out for a night here and a night there, and realized it’d be a stronger experience if I turned it into a multi-day outing. Waking up and going to bed within the same experience exponentially enriches that experience. I developed it to the point where I was dropped off on the other side of Austin without a phone, money, or ID and gave myself 5 nights (sleeping during the day) to wander back to my house.

It was such a departure from my day to day life. It also raised interesting questions, like where to sleep. I did pack all the food that I ate for 5 days and allowed myself to ‘forage’ for water. I’m out there trying to make this aesthetic art thing, but basically living as a street person, which puts me at odds with the majority of people in the city and how they view their surroundings. I realized a different set of rules as to how I can and should operate. My goal was to gain the greatest amount of freedom in order to explore the urban environment in abstract terms of light and space. It was incredibly insightful.

I’m really interested in the perception of place and the relationship between people and their environments.

How did you establish and evolve your personal vision?

Never being satisfied is certainly one method. Exploring various processes and letting the process speak will also push that envelop. I’m continually playing with a new process or challenging the assumptions of what I take for truth. exploring something else. There’s also a process of self understanding that has to occur too. That just comes with making work. It’s not something that can be forced. Engaging in what you enjoy is a starting point.

Best career move so far?

I went to the Eddie Adams Workshop in 2008, and that has been as pivotal as any career juncture as it immediately put me in touch with a strong photo community and some talented colleagues/friends. I didn’t know any photographers when I first started shooting.

Career development is a pretty slow process though. I thinking being open to opportunity is helpful. There’s a fine line between developing something on your own and being open to something that comes along. I’ve been more focused on what kind of work I’m generating than how much. With freelance work, it’s easy to keep yourself busy chasing to keep the wheels going and you have to be comfortable with the ups and downs of freelance life and balancing art and commerce.

Do you have any hobbies outside of photography?

Too many. Lots of sports: skiing, climbing, hiking, biking, baseball, basketball, whatever comes along. I swim a lot in Austin, primarily at Barton Springs. I’m on a sandlot baseball team/social club – The Texas Playboys. I grew up playing baseball and pitched in college. Pitching is one of the most enjoyable things I know. I’ve always enjoyed working with my hands and body. During the past two years I’ve been building out a trailer as a autonomous studio space. That is more of a design project than a photographic one.

I always find it enjoyable working on something physical and bringing that into the photographic process. I think good photography comes out of that.

Favorite thing about shooting in Texas?

I like exploring the Texas mythology and how the idea of Texas and reality of Texas can be quite different. I grew up in Georgia and it took me a couple years to get accustomed to the culture, mythology, and contemporary landscape of Texas, but at this point it’s a part of me. The state has some bravado. It’s a really fascinating and diverse place. I think anything with a really strong culture is rich territory for a photographer. There’s a rich mythology, and there’s no shortage of interesting people. There’s also a freedom in Texas where people are continually re-inventing themselves and what Texas can be. It’s an evolving place.

I think about it now as a lifelong pursuit… Don’t feel like you need to prove your work too quickly…

Advice for anyone just getting started?

It really took me a long time to get my career going, primarily because my background was not in photography. Part of that was my youthful impatience and not understanding what all goes into operating a photo career (as opposed to just taking a photo). There is a ton of accessible photography out there, but it’s not all professional. I always thought my images were good enough and I should be further along than where I’m at, but I don’t think is a beneficial thought. There was a long gestation period, so I’d say, don’t rush it. One of the speakers at the Eddie Adams Workshop retold a quote (I’d have to dig around quite a bit to find out who first said it): “Do what you can with what you have where you are.”

I think about it now as a lifelong pursuit – photography is something I’ll always practice and it will take different forms. Don’t feel like you need to prove your work too quickly, The more time you spend with the work and putting your effort into refining your work, will strengthen what the work is. That’s something I still tell myself. If you don’t know what you want to say and why, you’ll get chewed up by the industry.

On the business side, find people you really want to work for. Find clients that you will willingly go beyond what is required to get the job done, because that’s what it takes to make it and to be satisfied creatively. It’s not enough to just get the job done unlike other professions.