Austin-based editorial and commercial photographer Matthew Mahon recently took time out from assignment work and cycling to talk about how Instagram is changing the rules for photographers, dish on Phoot Camp and explain the dangers of riding a bike at 30 miles an hour.

I hear you just got back from Phoot Camp. What was that like?

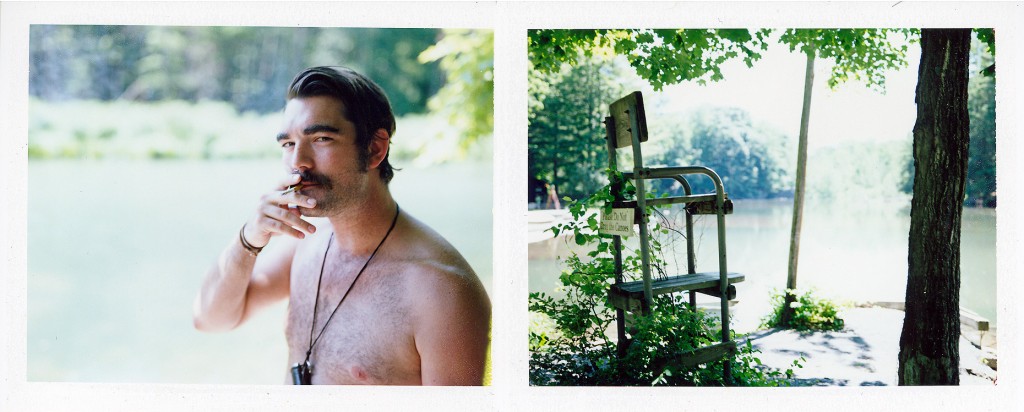

Phoot Camp is the brainchild of Laura Brunow Miner, who I met when she was the editor of JPEG magazine. Unfortunately JPEG couldn’t survive – it was a beautiful magazine – but Laura, steadfast and true to the component of great photography, decided she was going to start Phoot Camp. And what she did was she hand-selected 50 photographers throughout the world who had been submitting to JPEG and she invited them to come out to California. Thirty people showed up to the original Phoot Camp. It has since turned into one of the most creative, wonderful photo communities that exist today.

Explain how the selection process works.

The way you get in is you have to do a self-portrait and you have to write a 500-word essay on why you should be there. Nobody is guaranteed – not even the alumni – to get back in. You have to bring it. If you look at the self-portraits from four years ago to last year you can see how the level keeps improving. But the interesting thing is Laura sometimes understands that a certain photographer might work well in the community and pushes them through. It’s her vision. She’s like a John Szarkowski [the legendary Director of Photography at New York’s Museum of Modern Art].

I understand the Phoot Camp participants collaborate with one another. Photographers are typically more competitive than collaborative, so how did that work?

Right, it’s the antithesis of how most photographers work. And that’s what’s so amazing about Phoot Camp. It’s this community that all of a sudden comes together, embraces one another, brings costumes, lights. You need a tripod, you need a camera, you need a model, whatever…

The typical attitude is, “Let’s celebrate photography. We’re here just to take pictures. We don’t care. We’re going to shoot with Holgas, we’re going to shoot digital, we’re going to shoot with Hasselblad, we’re going to shoot 4×5.” It was wild. After that, I was convinced this was the community I wanted to be plugged into.

Visually I’m like a mathematician. I like to have a problem, and take the different pieces and put them together and try to figure it out. Sometimes it doesn’t work. Sometimes it fits magically.

Why is being part of a photographic community so important?

Because when we stopped shooting film, when we stopped seeing each other in labs all the time, and we all started sitting behind computers, we stopped communicating. We still communicate through email here and there, and now with text messages and on Facebook. But we used to actually see each other; we used to be physically there. If Wyatt McSpadden didn’t live across the street from me I’d never see him. But I used to see him in the lab all the time. When we were all shooting film, we were busy photographers and we’d see each other and we talked. Now we are all sitting in front of computers editing and retouching, removed from each other. The community has disintegrated.

You’re not from Texas originally. What’s your story? What brought you here?

I grew up in New Jersey right outside of Manhattan. I went to college at Rutgers. When I graduated in the early ‘90s, I had a bunch of friends that moved to Seattle. I moved out there 10 minutes prior to the grunge explosion, and lived through that whole scene. I always wanted to be a photographer, because that was my education. But at the same time I had this idea that I wanted to be an artistic photographer. So what I did was I tended bar, and I would invite bar patrons to these shows at underground galleries. We used to have these shows in this artist collective I was involved in where 500 people would show up, a lot of them people I’d given invitations to at the bar.

One of the women I’d given an invitation to ended up being an art director at an ad agency and she asked if I could come in and show her creative director a portfolio. Her name was Jo Dixon. I had no idea what an art director was. I had no idea what a creative director was. And I’d never heard of an ad agency, but I walked in and showed my portfolio. The creative director started gushing over this 15-picture book that I brought in. She was like, “Where did you find this guy?” They were talking about me like I wasn’t there. They thought I was perfect for this ad and offered me $2000 plus expenses. This was something I normally did for free. She asked if that was enough. I thought I was going to throw up on myself. I was a bartender because I wanted to maintain artistic integrity and all of a sudden I was just like, “Fuck it. Sell me out.”

My advice to any young photographer is to figure out for yourself how you want to be creative and run with it. Find what your passion is and just go. Don’t be traditional. Tradition will more than likely stymie you.

So why did you leave Seattle?

The girl I was with at the time was from Austin. She moved to Seattle for me. She hated it. It was grey, wet and rainy. She lamented leaving Austin. After seven years in Seattle I agreed to go back with her to Texas.

I came here, it was 1999. The economy was crazy. The high-tech bubble was expanding. I got in with a lot of the West Coast magazines. Zana Woods [longtime director of photography at Wired magazine] was the first person to ever hire me at Wired. I started shooting regularly for Wired and then all of a sudden Industry Standard, Red Herring, all those cool West Coast magazines that I thought were so much cooler than the Northeast magazines, because they had a different look, they embraced me. And because so much high-tech was happening in Austin, all these little Austin-based ad agencies were hiring me to shoot their ads, and it just exploded. That was one of my best years.

So did Zana give you your first big break?

Zana was definitely a part, but more so it was a woman here in town named Jennifer Taylor. She worked at this satellite office of Leo Burnett. She hired me to do a bunch of advertising. I was shooting for Wired. These high tech companies were advertising in Wired. It was a perfect marriage. For 12-14 months it was non-stop. I think I made $170,000 that year as a photographer in Austin, Texas, and I was 33 years old.

How did you learn to handle yourself on these big ad shoots, having not really learned that in school?

I had no idea. But at that point in time, the way the dot-com industry was working, there was so much stuff to be shot. Jennifer held my hand through it all. She’d call me three days before a shoot and say I needed to have catering, this, this, this and this. These are the people you need to call. Back then, when she would hire me to do one of these jobs, I wasn’t doing estimates like I do now. It was just like, “You’re it. We’re hiring you. Let’s talk money. This is what we can afford.” At that point I was shooting stuff for Newsweek and Wired for like $400 a day, so $3500 for a day of work – it was the most money I’d ever made in my life.

At first I was a photo assistant and I didn’t have a computer, so I was hand-writing invoices. That’s what we did back then. She said you CANNOT give them a hand-written invoice. So she did my first letterhead for me. Because, here’s the interesting thing at that time: there was so much need, and it was important for people like her to find talent to fit that need. If she could find someone who was unique it was all the better for her; it made her look better, even if she had to hold my hand and wipe my mouth because I had chocolate on it.

Is the key takeaway then to just focus on having a unique style and look and trust that the business side will come along in time? Is that the Matthew Mahon lesson?

No, do what you love. Period. If you don’t love it, don’t do it. Because if you don’t love it, you’re going to end up not liking it. Bottom line is you got to want it but you can’t be guaranteed that people are going to want to buy it. It’s cyclical. There’s no magic button you can push. Take Neil Young for example. He has had an undulating career. And what Neil has always done, is Neil has stayed true to who he wants to be. He has never sold out to anybody. He never did anything he felt like didn’t agree with who he was inside. I live the same way. If there are weeks I don’t want to be creative I don’t do it. If I want to watch movies and sleep all day that’s what I’ll do. But when I am inspired I dial it and I get in it.

So what gets you really inspired? What is your perfect assignment?

That’s hard to say because the majority of my career has been magazine work. I show up and photograph people I’ve never met in places I’ve never been. However, as difficult as that can be at times, it can also be remarkably surprising and rewarding. Because what happens sometimes is you walk into a situation and everything is working. You’re dialed and you figure it out. Sometimes it’s a bad situation and you figure it out but those times are usually not the greatest pictures.

The thing is, when anybody calls me to go take pictures I’m excited. It sounds ridiculous but if Texas Monthly calls me, if Time calls me, if People calls me, regardless of what it is, I get excited to work. When I show up, each time it’s a different situation.

Visually I’m like a mathematician. I like to have a problem, and take the different pieces and put them together and try to figure it out. Sometimes it doesn’t work. Sometimes it fits magically. Sometimes you work really hard at it and it fits together in some way you didn’t anticipate. I’m so sad that magazines are going away because I would shoot magazine photography for the next 50 years. I would die doing it.

Do you see any potential in websites taking on some of the commission work magazines have traditionally supplied?

When Martha Bardach was still at Time, she hired me to shoot specifically for the website. ESPN hired me once to shoot specifically for the website. Same pay. It felt different though. There wasn’t the possibility you’re going to see this double truck in the magazine. It’s going to be on the website. It’s not even going to be a quarter page of the website. It sucks. I don’t have an iPad but I have looked at some iPad magazines where they put additional photos in. It’s interesting. It’s different. Do I think that’s where it’s going? I don’t know.

Photography is always going to be relevant because people like to look at things. But are we still going to be getting paid? I don’t know. Look at Instagram. People can create amazing images with an iPhone now. And people get paid to do it. There are social media people at major companies that hire Instagrammers with big followings to do Instagram events. And they’ll pay them $700. They’ll pay better than Time magazine for a day rate to shoot a portrait, or to go photograph something with your iPhone. Think about that. Photography then becomes a vehicle. It becomes a very specific vehicle at that point to just reach the masses.

Instagram has totally changed the game. It’s like the new Facebook. It’s so hot now. That generation of Facebookers that got on at the very end don’t even know what Instagram is right now, that’s how hot it is. That’s how technology works. The older generation has no idea what it is. And it’s just this juggernaut that moves and it’s going very quickly. And it’s happening constantly but at the same time it’s going to spawn into this next thing. Where does this put us as professional photographers who try to hone our craft and light things? I don’t know. I have no idea. I’ll tell you one thing: If I could sync into an iPhone with a strobe, I’d do it. I’d do it in a minute.

What do you like best about being an Austin-based photographer?

I like being in Austin. I like not being in New York. I like that there’s a car parked right outside my front door that I don’t have to jockey for a parking position. I like living in a simple place. I almost brought my career back up to New York at one point and I’m glad I didn’t. I might have done better up there. But Austin’s a great city. Dan Winters is somebody that came here after he was Dan. Someone like Randal Ford became Randal out of Austin but at the same time Randal works harder than I want to work. I don’t want to work that hard, and that’s being honest. I like to work and I like to be creative. I like to be obsessed with photography in a healthy way but I also like balance. I don’t want it to dictate everything that I do.

I know fitness and biking specifically are big interests of yours. Is cycling your number one passion outside of photography?

I’ve always been a cyclist, but it was five years ago that I was riding and a friend of mine suggested I take up racing. I tried it and I really enjoyed it. I dedicated three years to it. The races I was good in are called criteriums – they call them crits. They’re inherently far more dangerous than road racing because you’re going around a circuit, you’re in a pack that’s constantly traveling at speeds upwards of 30 miles per hour, you’re bumping each other. So you have more potential to get taken down.

I crashed three times in my last season, and it was always other people crashing into me and taking me out. After the third one, I went down going 37 miles per hour right after I’d crossed the finish line. Someone actually crashed into me after we finished and took me down. I said, “I’m done. I’m not doing this anymore.” It was the most painful thing. I had road rash from my ankle all the way up to my elbow. You slide across asphalt at 37 miles per hour wearing the equivalent of pajamas for the reward of bragging rights. You tell me if it’s worth the risk. I was a Cat 3 racer when I stopped.

So I started touring, which is the greatest thing because you get to climb mountains, you get to see oceans, you get to see lakes, you get to see farms. You get to see parts of America that people don’t go to. That’s what I do. I choose parts of America that most people don’t drive to. And you find the most remote roads to ride on because you don’t want to ride with cars. And it’s amazing. It’s actually magical. I have a good buddy who goes out and joins me in the summer. It’s a great thing.

Which photographers have most inspired you?

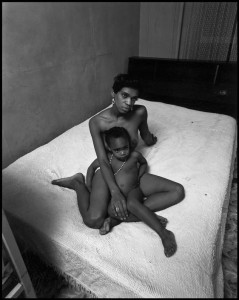

The original inspiration for photography was Bruce Davidson. My very first photography class I was taking at Brookdale Community College in New Jersey. My mom had signed me up for it. She was an administrator there. The teacher saw that I had a rather significant attraction for the medium. The class was like 30 people. It was about the 9th class of a 12-week course. My instructor’s name was Herb Edwards. And it was a three-hour class we went to. We’d get there a 7:00 and leave at 10:00 at night. I loved it and he saw that I loved it. It was 10:00, class was disbanding, and he grabbed me and this girl and said, “Hey, I want to show you two something. Will you stay after class?” So we went to this back room and he put up a slide projector and he showed us Bruce Davidson’s East 100th Street. We stayed there until 11:30 looking at this work. I just remember looking at that work and thinking, “This is what I want to do for the rest of my life. This is it.”

How old were you?

22, 21 maybe. I even went up to East Harlem and shot with my Pentax 1000 and did not get the same results, because you know Bruce Davidson was shooting with 4×5 or 8×10, whatever he was shooting. It was amazing though.

Dan Winters is another inspiration?

Yeah, once I started shooting commercial jobs and lighting things, I got clued into Dan early on. He was still in LA. I’d seen some of the celebrity stuff he’d done. I was always a New York Times Sunday subscriber, so I’d get the magazine. One of the greatest photographs I’ve ever seen was the Helen Mirren photograph on the cover when she won the Oscar that he shot for The New York Times Magazine. It’s beyond photography. I can’t even explain it. You look at it and you think to yourself as a photographer, I want to be that good. That’s what I want to do. I want to create things that look this amazing.

Harry Benson was somebody else who I was really inspired by. You could not have two more polar opposites. Harry literally walked in and shot. Dan walked in and very methodically built, and so I have these two different schools of thought about how I want to go about things. When I work I move fast. I exhaust assistants. I don’t exhaust them in a bad way where I’m mean to them, but I work them. I work a situation, and we move and we’re fast. I don’t build things. I sometimes am slow but once I get off tripod, and I always try to get off tripod, I move. That’s where I feel free.

What advice do you have for young photographers just coming up? You worked as an assistant. Is that a good way to go?

Sure, that’s a good way to go. But honestly in this day and age I have no idea. At Phoot Camp there were five different people that had over a million followers collectively that get paid to go Instagram with their iPhones. If I could show up to a job with my iPhone I would do that. If camera phones are going to become that good, that you can do it that way, why not? My advice to any young photographer is to figure out for yourself how you want to be creative and run with it. Find what your passion is and just go. Don’t be traditional. Tradition will more than likely stymie you. There was definitely a way to do it for a long time, but the game has totally changed in the last 10 years. It changes momentarily. We live in a world of social media now and it is constantly changing.

I have this friend who just started Instagramming three weeks ago. She’s already has 110 followers and she’s a commercial real estate sales person. She loves it, and she’s now getting her commercial real estate people to pay her. She actually shot a job today, one of her commercial real estate friends had seen some of her stuff on Instagram and he offered to pay her $600 to photograph one of his commercial properties. She’s doing it with her Blackberry and putting it on an iPad and her Blackberry is from 2004. It’s a totally different game now. My advice is, figure it out. It’s a weird time.

Are magazines saying you can’t put pictures from the shoot on social media before the story is published or does that go without saying?

For me, the era I came up in, I’d never do that. There’s been a few occasions when I’ve done that but it’s so removed there’s no way you can figure it out. I was shooting a job in Panama for Smart Money. On my Facebook I posted I was in Panama but I never mentioned what I was doing. People want to see that you’re shooting in Panama. But I would never mention I was there for a specific client.

But here’s an interesting thing. I recently did a shoot for Circuit of the Americas, the new Formula One racing track that’s opening here. They called me to do their first print advertising campaign that came out in the Wall Street Journal and USA Today. As we were shooting it, they had these guys that brought the car there. They were all Instagramming and they were Facebooking. I was as well and the art director was in support of me doing so. It was weird because this is not how it normally goes but it was smart. I got so much attention from that and so did they. Every one of those pictures – I took three that day – every one of them had 80 likes. For 80 likes you got to think other people are looking at it. Huh. That’s a different way to approach it. Just throw it all out there the moment it’s happening.

People in this day and age want to see things now. And it’s that fleeting too. When you Instagram something and it gets 100 likes in a day another few likes might trickle in over the next week and then it’s dead.

It’s just buried in the avalanche.

What does that mean for imagery? I don’t know. There was an interesting article written by a guy named Nate Bolt: Why Is Istagram so Popular: Quality, Audience and Constraints. It was very intentional the way they built the application and why they did it that way. You can’t shoot five pictures with Instagram and then go on your phone and edit. You have to commit to it at that moment. If you commit to it you have to upload it and if you don’t like it you have to delete it. They did that intentionally. They wanted it to be that way. They wanted you to not be able to create portfolios. That’s why it’s Instagram and not Latergram.

**********

Follow Matthew on instagram: @mahon_

**********

Jay DeFoore (@jdefoore) has served as an editor at Photo District News (PDN), Editor & Publisher, American PHOTO and Popular Photography & Imaging.